Ransomware has become one of the most well-known tools in the cybercriminal’s arsenal. It has demonstrated its ability to disrupt any business and community, regardless of its size and level of security, ranging from an international shipping group brought to its knees by the encryption of its production tools to the death of a patient during a transfer between German hospitals. But how did we progress in 30 years from a malicious program on a floppy disk, demanding a ransom of a couple of hundred dollars, to a fully-fledged, multi-billion-dollar criminal industry with its own structure?

We examine the history of ransomware and the evolution of the phenomenon.

The genesis of ransomware (1989-2006)

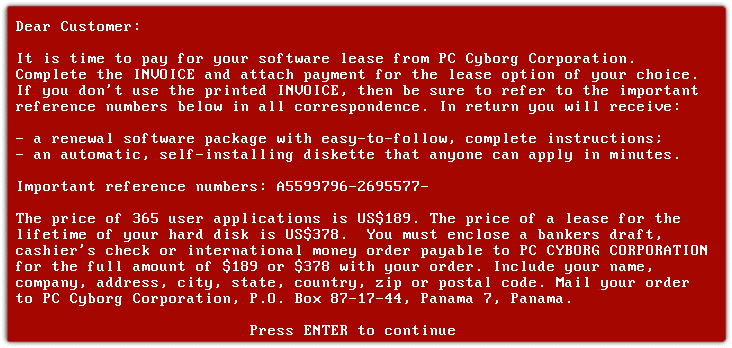

Contrary to popular belief, the very earliest ransomware did not appear with the internet. The (inglorious) history of malware began in the late 1980s, with the sole purpose of locking up workstations, before spreading to affect individuals and companies with microcomputers. In 1989, the “AIDS Trojan” was the first ransomware in computer history. So, who invented ransomware? At a time of concerns about the emergence of the AIDS virus, biologist Joseph L. Popp sent 20,000 floppy disks containing information about the disease to patient groups, medical institutions and private individuals in 90 countries. But although the disks did contain information on that topic, they also contained a virus that encrypted files on the infected machine after a certain number of restarts. To receive the decryption software, victims had to pay a ransom of $189. The number of compromised machines is still unknown, but Joseph Popp was arrested by the FBI before being declared psychologically unfit to stand trial.

Figure 1: AIDS Trojan ransomware interface (source: en.wikipedia.org)

Despite this shock development, it would actually be DDoS attacks and worms that would grab the headlines in the following period. This is because ransomware could be relatively easily tracked from the payment information. The ransomware that would follow therefore took almost 15 years to emerge, in connection with the arrival of digital currencies and then crypto-currencies, offering more streamlined ransom payments and currency exchanges, as well as a degree of anonymity. Such ransomware has but one function: to sabotage data by encrypting all the files on the disk without impacting the functioning of the operating system itself. This left victims with access to their operating system, yet without being able to use any of the files on it. In 2005, PGPCoder (or Gpcode), nicknamed the “$20 ransomware”, was one of the first examples of ransomware distributed online. It aimed to infect Windows systems by targeting files containing commonly-used extensions such as .rar, .zip, .jpg, .doc and .xls. In 2006, the Archievus ransomware made decryption attempts incrementally more difficult by adopting the RSA encryption algorithm, using an asymmetric public and private key mechanism. Targeting users' personal content stored in the "My Documents" file in Microsoft Windows, this ransomware then placed a file entitled "how to get your files back.txt" into the same directory. Analysts and cybersecurity experts later discovered that a single 38-character password could be used to decrypt any infected file ("mf2lro8sw03ufvnsq034jfowr18f3cszc20vmw", which was not exactly easy to guess...). This deprived the Archievus ransomware of its extortion power.

Wider spread of ransomware with the adoption of the internet (2007-2016)

In the first half of the 2000s, internet adoption grew relentlessly, with nearly 87% of Americans online by the end of 2014. Messaging, social networks, forums and peer-to-peer networks provided the foundation upon which the WinLock ransomware and its variants would spread widely from 2011 to 2014. With its signature characteristic of not encrypting the data on the infected computer, this ransomware had the function of blocking access to the machine by displaying a window containing a pornographic photo and a request for payment using a premium SMS service. Called “Locker”, this first evolution in ransomware aimed to prevent the operating system from starting up.

Following this success, variants masquerading as law enforcement organisations would appear. This was the case with the Reveton ransomware in 2012, which posed as the FBI agency, locking its victims' computers and demanding payment of a $200 fine. This ransomware was widely distributed on peer-to-peer platforms and pornographic sites. Internet users then paid quickly to avoid any reprisals linked to copyright infringement or the distribution of pornographic content. After that, ransom demands were to become more and more creative to increase their chances of payment.

The first technological revolutions in ransomware (2013-2016)

The year 2013 marked a technological turning point with the CryptoLocker ransomware and its attacker-controlled “command & control” server. “Via the use of a command and control server, the group of attackers can hold discussions with the victim, and negotiate, extend or reduce the time before data destruction. They have the ability to put additional pressure on the victim and increase their chance of payment,” explains Pierre-Olivier Kaplan, Stormshield Research & Development Engineer. In conjunction with huge-scale blanket campaigns, cyber criminals can then remotely control the virus loads on infected machines while negotiating with the victims. This new strategy paid off: CryptoLocker generated $27 million in its first two months of operation. It should also be noted that this was one of the first ransomware programs to demand a Bitcoin ransom.

In 2014, the attack front widened with the first attacks against Android tablets and mobiles. The SimpleLocker and Sypeng ransomware were spread through fake Adobe Flash software update messages. The following year, users of Linux operating systems were targeted, this time by the Encoder ransomware.

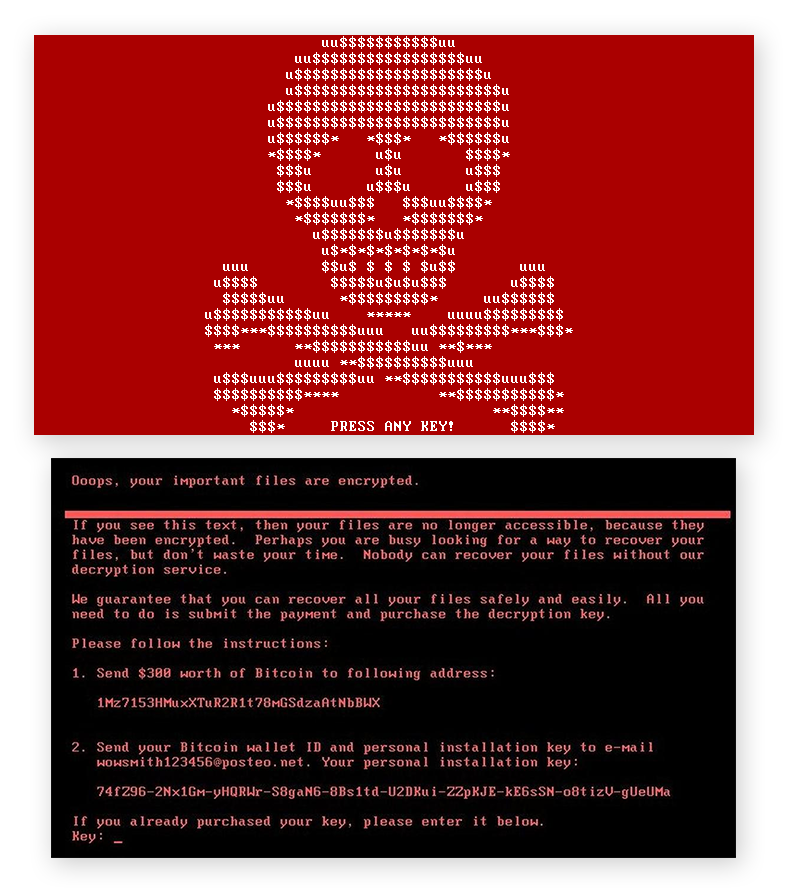

In 2016, Petya paved the way for phishing attacks by targeting business email addresses. Hidden inside a Word or PDF document, victims activate the ransomware themselves when opening the file (thus “detonating” the malware’s payload). This ransomware not only blocks access to certain files, it also locks the entire hard disk by encrypting the master file table. A red skull and crossbones appears on the screen to demand payment of the ransom. In addition to the psychological effect on victims, this graphic depiction of ransomware would be picked up by the traditional media, raising awareness of the cyber threat among the general public.

Figure 2: Petya ransomware interface (source: avast.com)

The emergence of state-sponsored attacks with global scope (2017-2018)

The years 2017-2018 marked a disruptive new development in the spread of cyber attacks. Thanks to the publication of Zero-day vulnerabilities stolen from a US government agency, ransomware attacks acquired the technical ability to spread massively across coexisting networks between one company and another.

In 2017, WannaCry was arguably the highest-profile ransomware. In just a few weeks, it affected 300,000 computers in 150 countries, spreading across Microsoft Windows operating systems through the EternalBlue vulnerability. Via the famous skull and crossbones displayed on their screens, companies would see the ransomware spread from site to site in a matter of just minutes. In the opinion of Nicolas Caproni, Head of the Threat & Detection Research (TDR) Team at SEKOIA.IO, WannaCry was probably launched a little too early. As a result of its lateral displacement abilities, its authors lost control of the ransomware, which infected as many machines as possible. With hundreds of thousands of companies falling victim to this ransomware, and given its uncontrolled spread, companies everywhere invested heavily in data backup and recovery products. In response, the cyber criminals would then also attack the backup points and simply delete them. This ensured that the data could not be restored – unless the ransom was paid.

Subsequently used as a weapon in state conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the NotPetya ransomware had the particular characteristic of reusing core elements of WannaCry, such as the exploitation of the EternalBlue and EternalRomance vulnerabilities and also lateral displacement – two vulnerabilities stolen from the NSA a few months previously. Although a patch had been released by Microsoft a few weeks earlier, this ransomware demonstrated administrators’ inability to update their systems quickly to deal with this attack. But “the ransomware was just a front,” according to Pierre Olivier Kaplan. “The real purpose of NotPetya was not extortion, but the destruction of data on a very widespread scale, with whole countries being targeted. These serious geopolitical implications resonate even more today as NotPetya, purportedly in the hands of Russian cybercriminal groups, has been targeting Ukraine.” By deleting data, this ransomware was being used not as a means of extortion, but as a weapon of digital destruction. This ransomware also camouflaged attempts to sabotage the Ukrainian metro, Kiev airport, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, and Ukraine’s central bank and national energy company. By the end of 2018, the U.S. government had estimated the damage attributed to these two attacks at more than $10 billion, according to Cyber Cover.

The era of Big Game Hunting (2019-2021)

By late 2019, the number of ransomware incidents had increased by 365%. In order to remain undetectable to security tools, cyber criminals opted not to launch large-scale campaigns – as had been the case with WannaCry – preferring instead to target large companies. Called “big game hunting”, this new strategy describes a modus operandi based on the recognition of the target's environment and the development of advanced attack scenarios. Attacker groups then study their target to tailor their ransom demands, as Nicolas Caproni explains: “Studies show that attacker groups do their homework on their targets. For example, they can exfiltrate financial documents to check whether cyber insurance has been taken out and to what value, in order to increase their chance of a ransom payment. Some groups are even thought to have people dedicated to analysis and negotiation. This new strategy has been a profitable one, as the average ransom demand tripled over this period, from $13,000 to $36,000.

By late 2019, the number of ransomware incidents had increased by 365%.

It was during this period that the double extortion mechanism was introduced. This mechanism has proven to be a formidable one: the targeted company is not only hit by the ransom demand, but is also threatened with the resale of its data on the darknet. In this way, disclosing part of the stolen critical data can be decisive in convincing targeted companies to pay the ransom, most often in the form of source code or customer data. And the mechanism can even affect the customers (or patients) of the affected organisations, with some cyber criminals even threatening to disclose the stolen personal data. In October 2020, patients at a psychotherapy centre in Finland were among the first to learn this lesson the hard way. The group of cyber criminals alleged to have created the Maze and Egregor ransomware were among the first to use this new mechanism. In addition to the technical aspect of ransomware, this group was characterised by constant communication with its victims in the form of pressure to pay in a short time and threats to disclose data. And this strategy paid off: by the end of November 2020, 300 companies are believed to have fallen victim to the Maze ransomware. A few months later, the Egregor campaigns counted more than 200 organisations among their targets, with an average of $700,000 in ransom payments per victim, according to ZDNet. The data disclosure mechanism was then used by Sodinokibi, commissioned by the REvil group.

In 2020, the big game hunting approach was to intensify with Darkside – which is technically similar to REvil – and an attack against the American oil transport and distribution giant, Colonial Pipeline. A ransom of 5 million dollars was then extorted. The following year, the FBI reported seizing ransom money to an equivalent value of $2.3 million in Bitcoin following a large-scale operation against the same group. In March 2021, the manufacturer Acer was presented with a demand for a record sum of 50 million dollars. In May 2021, IT solution provider Kaseya fell victim, affecting over 1,500 of its customers. The ransom demanded on that occasion was 70 million dollars.

Increasing structure in the cyber-crime sector (2021-2022)

One of the latest revolutions in the modus operandi of cyber criminals has been the emergence of ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) platforms. This provides less experienced attacker groups with access to a complete infrastructure, offering the benefits of ready-to-use ransomware campaigns. The platforms provide their malicious solutions for hire, and may also collect a percentage of the ransom recovered from victims. Some attacker groups, who have invested in ransomware research and development, then create franchises for marketing their ransomware to other criminal groups. One such example is the Conti ransomware franchise. This group trains “junior” staff, offering them a fixed salary and a profit-sharing scheme.

According to Pierre-Olivier Kaplan, the success of “ransomware-as-a-service” platforms is also leading to increasingly sophisticated malware: “By the end of 2010, ransomware was on the wane because ransom payments were unsecured and could be traced back to criminal networks. With the proliferation and advent of crypto-currencies that provide a degree of anonymity in ransom payments, money transfers have become almost ‘safe’ for attacker groups. In addition, between 2010 and 2020, there were various improvements in propagation mechanisms. From Lockbit and DarkSide to Laspus$, they are extremely sophisticated. They have been boosted by this entire decade of continuous improvement in their replication mechanisms, their communication mechanisms with a control server and all their ancillary activities – that is to say, data theft. Over the last few years, the objectives have remained the same. But their management and execution methods are increasingly ambitious. As a result, ransomware has become ubiquitous. ”

In 2021, the role of Initial Access Brokers (IABs) is emerging in the cyber landscape. Specialising in corporate intrusion and initial access, they provide a way into corporate networks for other malicious groups to use for their own attacks. Compromised credentials, brute force attacks, and exploitation of vulnerabilities… these are the means by which these initial access resellers gain access. “As ransomware operators become the most reliable partners of IABs, they are acting as backdoor buyers and thus outsourcing the first stage of their intrusions," Caproni explains. For example, ransomware actors had access to more than 1,000 access lists offered for sale by IABs in the second half of 2021, according to a study by SEKOIA.IO. This new role among attacker groups represents just as great a threat as ransomware. “Initial access brokers and the resale of access are the upstream business of ransomware, continues Nicolas Caproni. This is a major threat. Ultimately, limiting ransomware would entail disrupting the IABs, ensuring that they no longer have back doors to infiltrate organisations.”

Ransomware: a never-ending story? The list of ransomware is already quite a long one: to date, the French authorities are tracking no less than 120 different families of ransomware. And with the emergence of new technologies (Web3, NFT, autonomous mobility) and the return of geopolitical conflicts, new forms of cyber threats are to be expected. The story of ransomware is therefore (unfortunately) far from over.