The year 2021 was an annus horribilis for IT subcontractors. Cyber attacks against Gitlab, SolarWinds and Kaseya demonstrated that service providers can be a vector of infection, impacting tens of thousands of customers worldwide. At the same time, there are many subcontractors on the OT side, with a responsibility for facilities maintenance and operation. With industrial networks that are sensitive by nature, the situation is an explosive cocktail. But how to anticipate and protect against it?

Here are some answers to the question of subcontracting security in the OT.

OT subcontracting: a surplus of risks to be considered

The first important question here is: who are the subcontractors in the OT world? Industrial subcontractors are called on in situations when the principal does not have the skills or capacity to intervene alone. Integrators and other maintenance companies are the traditional stakeholders, and are still perceived as weak links in the OT environment security chain. But in reality, other subcontracting actors can also be a threat; such as, for example, design offices and suppliers of components or subsystems. They are in contact with industrial companies, forming part of the subcontracting chain, and are therefore by analogy a target for cybercriminals. Because they are involved in system specification, design, development, integration, commissioning, validation and maintenance work, they are required to share confidential documents when suppliers are connected to the information system of the target company.

The importance of the question of cyber-maturity of subcontractors in the OT is becoming more central than ever. The historical lack of adoption of good cybersecurity practices has contributed to the current fragility of these players – whose job is to manage the operation of their own automated systems – and by extension, those of their industrial customers.

In light of the events of 2021, the importance of the question of cyber-maturity of subcontractors in the OT is becoming more central than ever. The historical lack of adoption of good cybersecurity practices has contributed to the current fragility of these players – whose job is to manage the operation of their own automated systems – and by extension, those of their industrial customers. Each link in the chain can then become a vector of infection for the rest of the industrial chain. All the more so when, due to a lifespan lasting several decades, the existing teams lack detailed knowledge of the history of equipment modifications (such as component changes, the addition and removal of PLCs, and even the loss of logs of modifications to production architectures). Inventories and mapping are rarely retained for long periods of time, resulting in risky situations in which Shadow OT spreads in industrial environments. A classic example is the integrator who buys a 4G router from a department store to maintain the installation, having no other way to download updates...

But it must also be recognised that this responsibility must be shared by industrial companies that do not impose (sufficient?) cybersecurity requirements on them. While physical access by subcontractors may be controlled on industrial infrastructures, their digital equivalents do not (yet) use the same approach. And the methods and tools for monitoring and controlling remote access are still too often lacking in practice.

A set of standards and benchmarks for OT subcontracting

However, to ensure a certain level of maturity among subcontractors, OT security managers can rely on a number of cybersecurity best practice standards.

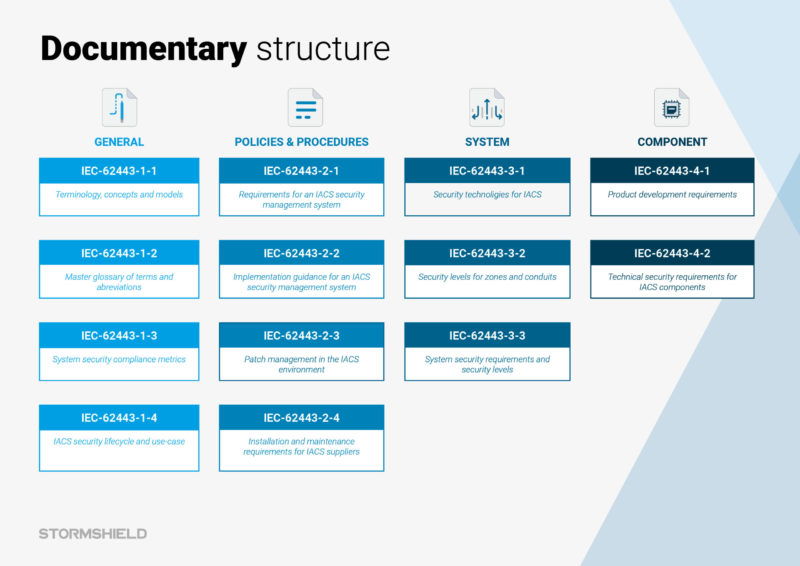

The best known of these in the industrial world is undoubtedly IEC 62443. It is a pragmatic standard dedicated to cybersecurity in industrial environments, offering best practices and assessing the level of maturity of industrial components. More specifically, IEC 62443-2-4 describes security requirements for all service providers, covering a dozen topics that span remote access, wireless and configuration management issues. But OT security managers can also rely on standards drawn from IT, such as ISO/IEC 27001. This standard is dedicated to managing information systems, and defines the requirements for the implementation of an ISMS (information security management system). The methodology of this standard enables the identification, assessment and handling of cyber risk through a management plan. ISO/IEC 27036 is from the same family, and is an international standard dedicated to customer-supplier relations. It establishes rules for securing an information system within the context of data exchange with a third party. All these standards provide structure for the industrial sector and enable considerations and organisational and operational challenges related to cybersecurity in OT environments to be taken into account. For its part, France’s ANSSI has also published a reference framework entitled “Cybersecurity requirements for industrial systems integration and maintenance providers”. Although first published in 2016, it is still relevant today.

The documentary structure of the IEC 62443 standard.

But how do you ensure that your chosen subcontractors adopt good cybersecurity practices? This is a central issue that must be addressed at the tender stage. One of the first actions required is to choose your service provider carefully by assessing its level of security during the presentation. To do this, it is imperative that the client's CISO is in attendance, and that it is possible to verify that good cybersecurity practices are being incorporated and implemented as part of the technical and organisational functions of the subcontracting company. This evaluation stage can also be implemented through a security audit by an independent service provider. These audits should be regularly carried out every year or two for all providers. Another way to ensure the quality of a provider is to specify requirements in the contractual relationship. In calls for tender, meaningful clauses on the integration of cybersecurity requirements must be included. These clauses must, for example, contain the requirements for the application of an ISSP (information system security policy) at the subcontractor's premises, and for raising awareness of cybersecurity issues among the teams that install and maintain the equipment on site. The identification of a cyber contact person is also essential, as is the presence of an SLA (service-level agreement) specific to the security patching. Lastly, these clauses must include a description of the method of communication between the subcontractor and its client in the event of a security incident. All these points (and others) should be an integral part of the score awarded to each service provider, before final approval and validation by the CISO of the company issuing the call for tender. The ANSSI's PAMS reference framework is a valuable aid in drawing up your specifications for administration and maintenance service providers.

OT subcontracting: a responsibility for industrial companies

But the question of the security of the subcontractor chain must also be taken into account by manufacturers. There are several levels to this process.

At the equipment level, some manufacturers are already implementing an internal self-certification phase prior to the installation of any new equipment or system. This practice enables the certification of the conformity of the industrial machines received, based on specifications developed by the actual customer. These specifications contain the rules and best practices for cybersecurity. Combined with an MCS (security maintenance) agreement, the customer has the ability to ensure that they do not incorporate vulnerable equipment or systems into their production environment. Secondly, from an organisational point of view, it is good practice to appoint cybersecurity contacts whose task is to ensure that the rules of the ISSP are applied in the production environments of each plant. This person may be a plant manager or an automation specialist with an interest in and knowledge of network management, relieving the load of the CISO, who cannot be physically present every day at the various industrial sites. In addition, and in order to mitigate the “Shadow OT” phenomenon, it is also advisable to map the flows and the various items of equipment and components used in the industrial environment. Mapping is performed using probes that discover and inventorise the items present on the networks. To cope with the many changes in the production environment, this mapping must be updated on a regular basis. In addition, teams must be prohibited from connecting additional network equipment and thus bypassing the IT department, believing that this will save time.

Last but not least, before imposing rules on subcontractors and suppliers, it is imperative to set up the infrastructure to accommodate them. The most common actions are the creation of one DMZ (demilitarised zone) per provider, the provision of VPN access, and the implementation of secure remote control tools. Access control mechanisms or a data filtering solution known as DLP (Data Leak Prevention) then ensure that the data exchanged with the service provider is indeed legitimate.

In response to this need for support, several initiatives have been developed in recent years. On the training side, France’s Institute of Regulation and Automation offers CYB-OT training, a course dedicated to cybersecurity in industrial systems. At the same time, groups of industry players have also been formed, such as GIMELEC. This group is made up of industrial cybersecurity publishers, manufacturers and integrators. Its mission is to produce informational content for industrial companies with the aim of increasing the maturity of decision-makers on cybersecurity issues. As such, it has just published its first educational guide on OT cybersecurity for IT decision-makers.

The issue of security in subcontracting is therefore a combination of good practice and shared responsibility between the client and the subcontractor. This is a virtuous circle that must be maintained throughout the contractual relationship. This responsibility will be reinforced throughout the European Union in 2024, when the reform of the NIS Directive is applied to all subcontractors responsible for critical infrastructure. Under the NIS, company directors may be held liable and the companies themselves fined up to 2.4% of their total turnover. This will accelerate awareness of the need for players in the industrial sector to secure their information systems.